The war that established the independence from Britain of the thirteen American colonies took place between 1775 and 1783, and is improperly called ‘The American War of Independence’ when it should more correctly be referred to as ‘The American Revolution’ – for that is what it was, a revolution.

In the early 1760s relations between the government in London and the Colonies became even more strained than they had ever been. The London government was intent on taking measures to control everything in the colonies, and the colonists objected, though only verbally at first. They found it difficult to understand why they should be taxed without having proper representation, indeed any representation in London. Independence-seekers gathered in most of the coastal port towns, such as New York, Richmond, Virginia and Boston, Massachusetts.

Tension increased with the arrival of the Stamp Acts (1765) and the Townshend Acts of 1767. Then a cruiser called Gaspée, supervising customs laws, was burned and sunk. The Boston Tea Party enraged Parliament more, when a well-organised bunch of upper class Boston youths drsssed and made-up as Native Americans boarded English ships in the harbour and blackened the waters by hurling their tea cargo overboard. Parliament’s answer to this outrage came in the form of the Intolerable Acts, intended to punish all Massachusetts for the tea party. The quick reaction of the Bostonians produced the first Continental Congress in 1774.

In April 1775 actual fighting broke out between American colonial militia calling themselves The Minutemen and British troops. There were untidy battles at Lexington and Concord. Soon other military conflicts emerged at Fort Ticonderoga (May 1775) and the Battle of Bunker Hill. Meanwhile many colonial families who had never sought independence from Britain and did not want it at all, had set out for the Canadian border. In June of that year the Second Continental Congress elected English farmer George Washington as undisputed leader of the Continental Army. In July they also adopted the freshly composed Declaration of Independence.

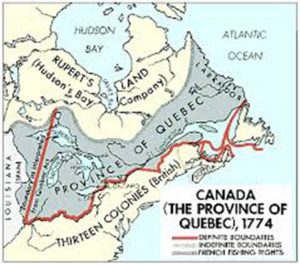

In June 1777 British troops were moving south from Canada, and the few small victories the Continental Army had achieved, plus the loss of the Battle of Long Island in August, 1776 made it seem inevitable that independence from Britain would never be achieved by force of arms. The, suddenly, the Battle of Saratoga took place in upstate New York, and the English general Burgoyne surprised everyone but himself by surrendering. This was the moment chosen by Britain’s ancient antagonist France to enter the revolution on the side of the colonists, by giving then material support, money and extra troops. Perhaps the French wanted revenge for having lost control of parts of Canada to Britain, including Quebec.

After another surprising surrender, this time by Lord Cornwallis in Virginia, British Prime Minister Lord North lacked his countrymen’s support for the war, and the Treaty of Paris (September, 1783) recognised the independence of what was now the United States of America. The anti-revolution colonists who had marched into Canada became the English-speaking core of that vast country, uniting businessmen, planters, farmers, medical practitioners and unabashed entrepreneurs, giving a structure to the most advanced political thinking of their time, whereas not a few thinkers doubted the victorious colonists’ ability to govern themselves, or even survive in this cruel and mendacious world. But the enormous new country was founded on a wave of genuine democracy, with an ideology of ‘free and equal rights for all’, and it not only survived, but toppled Britain off the perch as Top Country, as well as beginning the long decline of all monarchies.

Britain was ruled by King George III at the time of the American Revolution. This third Hanoverian suffered from intermittent bouts of madness, and it was during an attack of porphyria that he managed to lose the Thirteen Colonies, making way for the United States.

Leave A Comment