These internal conflicts that tortured the last century of the Roman Republic lasted from 88 BC to 28 AD and led directly (some would say inevitably) to the institution of of unchallengable authority in one man, or if not in one, in a Triuvirate.

Political life in Rome had been unstable from the period of Sulla’s dictatorship, and the Catiline Conspiracy (64, 63 BC). Then two really important names emerged: Julius Caesar and Pompey (q.v.). At first these two difficult, overpoweringly ambitious men had formed an alliance. Then Caesar defeated the armies of Pompey on the battlefields of Spain in 49, at Ilerda. One year later he smashed Pompey himself at Pharsalus, going on to win further victories in Asia and Africa.

The republican cause came to an end with the suicide (46 BC) of Marcus Porcius Cato the Roman statesman and philosopher, grandson of Cato the Elder. Cato the Younger had been unable to stomach Caesar’s victory at Utica in northern Africa. Though less famous than his grandsire, Cato the Younger was a fine example of traditional Roman and republican values. It is clear from his few diaries that he knew where Julius Caesar was heading – or at thought he was heading. The Ides of March were yet to come.

When he got back to Rome Julius lost no time in dictator and sole ruler, exactly as Cato and others had predicted. In the Senate in 44 BC he announced his plan to mount military expeditions against Dacia and Parthia, but he was (literally) cut short by outraged republicans (every one one of them patrician landowners) who murdered him.

Now it was indeed inevitable that civil wars should follow, because a number of equally ambitious men saw themselves as ‘Emperor’ and were more than prepared to fight for their own cause. These included Brutus, who may or may not have been an illegitimate son of Caesar, Marc Antony, a foul-mouthed and proficient soldier always popular with the legions, and the smooth-tongued, smooth-skinned, less than twenty-year-old Octavian who was Caesar’s nephew.

In 43 BC however the supremely clever Octavian formed the Triumvirate with Marc Antony and a washout called Lepidus, whose nose was for ever in the clouds; he was unpopular with the legions. Together they fought Brutus and Cassius, and defeated them at Philippi. Cassius was killed outright, and Brutus, an erstwhile member of the imperial family, was left to fall on his sword.

Marc Antony meanwhile had formed a romantic attachment with the Queen of Egypt, a clever, unscrupulous, long-nosed and equally ambitious woman fond of men and household pets such as snakes. Marc Antony fell into an abyss from which he would not emerge.

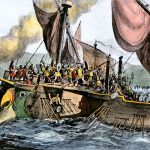

He went into battle against Octavian at Actium, was deserted by Cleopatra, and defeated. Shortly afterwards he fell on his sword too, rather than kneel before Octavian, and his corpse was hauled up to Queen Cleopatra’s rooms on a stretcher.

The Queen decided that life with Marc was intolerable and set about killing herself and at least one of her handmaidens with the help of those household snakes. Octavian is said to have been relieved, as he had not fancied an affair with Cleopatra, who could have been his mother. Instead, he annexed Egypt in Rome’s name.

Octavian, as we all know, became the Emperor Augustus (q.v.) who ruled well for a long time before dying mysteriously after eating figs which may or may not have been prepared for him by his wife the Empress Livia.

Leave A Comment