History embraces an Iron Chancellor (von Bismarck) and an Iron Duke (Wellington). Their descendents are still around, in the luscious form of Gunilla, and rotund form of the present Duke, formerly Marquess of Duero.

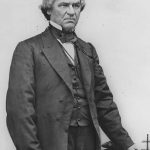

Arthur Wellesley was, as his name implies, Irish, born in 1769. He, like so many dozens of other men destined for leadership and fame, went to Eton, where there are schoolrooms and playing fields. More of the latter later.

He became the Earl of Wellington in February of 1812, Marquess in October of the same year, and Duke in 1814 when he was forty-five. But we are rushing the gun; he was first commissioned into the Army in 1785 at sixteen, a fledgling martinet with a biting wit and an acknowledged sense of fairness. He was also fully conscious of his own position. From 1796 to 1805 (the year of Trafalgar) he served in India, as administrator and soldier. But from 1805 to 1808 he preferred the House of Commons, where he sat as a Member for Rye in Sussex.

In 1808 however he was in uniform again, taking an army to Portugal. He defeated a French force in Portuguese territory, and having beaten them, allowed them to make an orderly and unhindered retreat to France. For this he was relieved of his post and ordered to a Court-Martial, though there was never any mention of cowardice. Wellesley had simply thrashed the French and sent them home, typical of his humour and sense of decency. The King of England, the Army councils and his peers however, thought he should have slaughtered the lot, a custom begun by King Richard I at Acre (qv). The Court-Martial exonerated him however, and sent him off to the Peninsular War again. He arrived in February 1809.

Now started a war of attrition between Wellesley and his allies the Spanish, against the best of Napoleon’s Marshalls and armies. The allies won battle after battle, though Wellington did not hold a high opinion of Spanish military discipline, and the Spanish, ever eager to cut throats, found Wellington stuffy and difficult, sticking his famous nose into everything. Spanish historians are convinced that Wellington was merely present at the battles of Vitoria, Salamanca, Ciudad Rodrigo, Fuentes de Oñoro, Talavera, Burgos, Vitoria and Orthez. English historians tend to take the opposite view.

Be that as it may, the combined force drove the French armies out of the Peninsula and Napoleon’s brother Joseph out of Madrid. For this the Spanish Cortes awarded Wellesley the title of Duque de Ciudad Rodrigo, Marqués de Douro and Conde de Vimiero, while the Portuguese made him Duque da Victoria and Marquez de Torres Vedras. Andalucía made a present of a magnificent finca at Illora to go with his Ducado.

Wellesley attended the Congress of Vienna as Duke of Wellington, and was in command of the British troops at the Battle of Waterloo, directly opposed by Napoleon Bonaparte himself, who had returned in triumph to France after having removed himself from an imposed exile on the island of Elba. Wellington was hard-pressed, and the battle might have gone the other way were in not for the unexpected arrival of Blucher’s Prussians, who Bonaparte had thought already beaten.

By 1819, loaded with honours and titles mounting up in piles, the Duke was in politics as ‘Master of the Ordnance’ in (PM) Lord Liverpool’s cabinet. In this office he was able to undertake diplomatic missions, which he liked very much, notably at the Congresses of Aix-La-Chapelle and Verona. In early 1828 he agreed to form a government, and was Prime Minister until 1830. He was a strong opponent of parliamentary reform, though as a good Irishman he accepted Catholic Emancipation. As he was no liberal, he was unpopular in Parliament, but enormously popular with the British people, who venerated him with the nickname ‘Old Bony’; they surrounded his house, Apsley, near Buckingham Palace, hoping to catch a glimpse of their ‘hero of Waterloo’. As an elderly man, he was also popular with Queen Victoria after her accession. He died at eighty-three, as erect, slim and muscular as he had always been. He did indeed say the famous phrase attributed to him by historians – itself a tribute: ‘the battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton . . .’

The wellington boot is said to have been designed and first worn by him.

Here are some of his quotable quotes:

“All the business of war, and indeed all the business of life, is to endeavour to find out what you don’t know by what you do; that’s what I called ‘guessing what was at the other side of the hill.’”

“I don’t know what effect these men (the Spanish Irregulars) will have on the enemy, but by God they frighten me.”

“I never saw so many many shocking bad hats in my life” (on seeing the First Reformed Parliament).

“If you’ll believe that, you’ll believe anything . . .” (on being accosted by a gentleman in the street who asked, ‘Mr. Jones, I believe?’

“I have no small talk and Peel has no manners” (a reference to Sir Robert Peel).

“Hard pounding, this, gentlemen; let’s see who will pound longest” (during the Battle of Waterloo)

“Publish and be damned!” (In reply to a blackmail threat – Wellington was a considerable and famed ladies’ man)

Leave A Comment