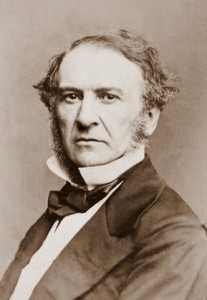

William E. Gladstone lived from 1809 – 98, was Prime Minister four times (1868 – 74, 1880 – 85, 1886, & 1892 – 4). His father was a North Country merchant rich enough to send him to Eton. He was the first, I believe of at least three generations of Gladstone Etonians; Charles G. was there from 1902 – 7 and was Master from 1912 – 46, and there was also an Ernest. At school William G. was popular but stern; he remained stern all his life but lost most of his popularity during his four stints as Premier. He was disliked intensely by Queen Victoria, who said he always addressed her at their private meetings as if she were a public meeting.

He came to Parliament as a Tory MP in 1832 when he was thirty-three. He proceeded to oppose every reform proposed by the Whig (later Liberal) government, including the abolition of slavery and the Factory Act which was another kind of abolition of slavery. This kind of reactionary treatment of reform stayed with stern Mr Gladstone all his life, even when he joined Sir Robert Peel’s Cabinet in 1841 at the Colonial Office and the Board of Trade. He was a natural and real Conservative, anxious to maintain a hierarchical social order at every level. “I am,” he said once, “an out-and-out inequalitarian.” He thought of a man’s vote not as a right for all men (there were no votes for women) but as a privilege for those thought to have earned the right to it.

Gladstone continued some of Peel’s reforms however, by reducing one hundred and fifty tariffs and abolishing another hundred and forty, which indicate that sternness was diminishing with age. He was Chancellor of the Exchequer under both Lord Aberdeen and Palmerston. By 1861 he had almost completely abolished duties on imports, which allowed a flood of them into the country – not always a Good Thing. He believed good governments should be cheap, a policy which might remove barriers to economic activity. He did not at all support the idea that governments should provide expensive services.

Following the split in the Tories in 1846 (the reason was the repeal of the Corn Laws) he did not confine himself to either of the major parties between 1846 and 1859. Then he joined the Liberals (mostly ex-Whigs) probably because he intensely disliked the conservative Benjamin Disraeli (q.v.), and partly because both Liberal leaders, Palmerston and Russell were getting old and would shortly have to retire. He backed the right horse for Palmerston (q.v.) died in 1865, and Lord Russell retired in 1867, so Gladstone became Leader of the Liberals and in 1868 formed his first administration employing the slogan “ Justice for Ireland!” as he knew this would unite Irish Catholics, Radicals and Protestant Reformists. There were four and a half million Catholics in Ireland, and little more than half a million members of the Church of Ireland, which was disestablished in 1869, but one third of its wealth went into charities and education – a Good Thing. Generally speaking, Gladstone’s first ministry was one of the best in the nineteenth century, even if the man himself took little interest in reforms such as Forster’s Education Act which tried to provide elementary education throughout Britain, and those reforms which sought to make the armed forces efficient, as well as serious moves made to ensure that entry into the civil service would be by competitive examination. He hated the Licensing Act of 1872 which limited opening hours in pubs. In 1871 he decided to protect Trade Union funds but retained as criminal offences obstruction, intimidation or threat. This pussyfooting made the trade unions nervous and unsure of themselves.

In the 1874 election Gladstone was defeated and resigned as leader of the Liberals, saying he would only return to politics if needed ‘to arrest some Great Evil’. Disraeli’s support for Turkey in ‘The Eastern Question’ (q.v.) was in William’s opinion that great evil, and he fought Disraeli’s foreign policy in 1879, leading to William’s second administration in the middle of an agricultural depression. Then the Irish Land War of 1879 – 82 threatened British control of that island. Gladstone promptly passed an Irish Land Act, but it failed to diminish support for the Nationalists. The third Reform Act gave the vote to all male householders – if you were male but did not own a property you couldn’t vote – but at least this now meant that two-thirds of all adult males had the vote, which was considerably more than before.

Outside Britain Gladstone was surrounded by problems which led to his further unpopularity. The Boers in South Africa for example tried to recover independence they had lost in 1877, by indulging in the First South African War (1880,81). The British forces were knocked out by the sharp-shooting Afrikaners at Majuba Hill. Gladstone decided to grant independence to the Transvaal rather than send out expensive armies for revenge. but he did send a British force to Egypt to put down a nationalist revolt. This was successfully quelled by Generalk Wolseley, but then the Mahdi revolted in the Sudan and Gladstone found he could not withdraw from Egypt so easily. General Gordon (q.v.) was ordered to withdraw Anglo-Egyotian forces from the Sudan but was himself killed in the fall of Khartoum by the Mahdi, and of course Gladstone took the blame.

Gladstone, troubled but still there, decided that Home Rule must be awarded to Ireland but when he introduced the bill it split the Liberal Party and the bill was thrown out. This led to one third of Gladstone’s supporters leaving the Liberals and eventually joining the Conservatives. He was out of office from 1886 – 92 and made no attempt to reunite the party, saying according to Lord Roseberry that he was not in touch with ‘new things’. But the Liberals returned to power in 1892 and William found himself Prime Minister again, his last ministry; unfortunately he became obsessed with Ireland (not the first English statesman to suffer this obsession), and thus became, like his obsession, a millstone tied to the neck of his party. He managed to get another Home Rule Act through the House of Commons in 1893 when he was well over eighty years old, but then the Act was rejected by the House of Lords. Both Queen Victoria and William’s colleagues were relieved when at last Gladstone retired. He died two years before the end of the nineteenth century.

Leave A Comment